October 31, 2023

Building a smarter shunt for hydrocephalus patients

Despite modest improvements since their invention in the 1950s, today’s shunts remain highly prone to failure. Madison Scientific plans on using a SmartShunt System to change that reality.

Angela and Chris Batterman of Pewaukee, Wisconsin keep their phones within arm’s reach 24/7. They never know when their 21-year-old son, Joseph, a highly accomplished student at the Milwaukee School of Engineering, may suddenly need to get to the hospital for something he has already experienced 25 times in his life — brain surgery.

An architectural engineering major, Joseph lives with an incurable condition known as hydrocephalus, in which excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) builds up around the brain instead of automatically flowing back into the blood stream.

Too much CSF increases intracranial pressure (ICP), causing intense headaches, nausea, vomiting and death if not treated on time. Unfortunately, the only treatment available for hydrocephalus is brain surgery. Once a patient is diagnosed, a neurosurgeon implants a shunt that allows the excess CSF to drain through a tube to the abdomen, relieving the increased ICP.

Despite modest improvements since their invention in the 1950s, today’s shunts remain highly prone to failure, primarily due to obstruction of the catheter implanted in the brain ventricles. When the shunt fails and symptoms are severe enough, a patient can go from feeling fine to a coma within hours.

“Nearly 40% of shunts placed in children fail within one year,” says Joseph’s UW Health pediatric neurosurgeon, Dr. Bermans “Benny” Iskandar. “About 50% fail within two years and the majority fail within 10 years.”

UW research team pinpoints cause of shunt failure; new company begins developing a smart shunt

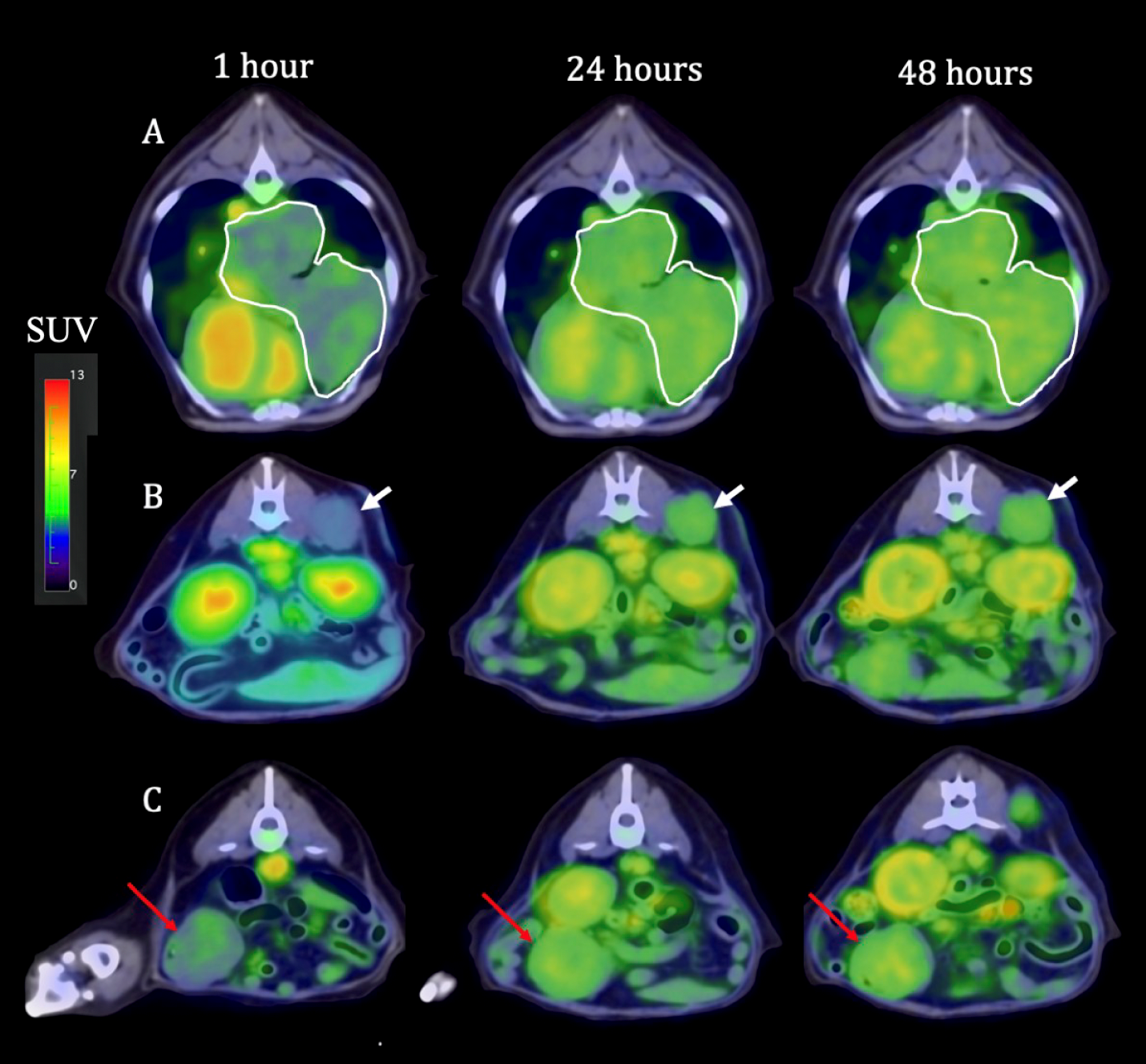

Thanks to the tireless efforts of Iskandar, a UW-Madison professor of neurosurgery and pediatrics since 1997, an answer to the problem of failing shunts may not be far away. For the past few years, Iskandar and several UW colleagues have been working to pinpoint the cause of shunt failure and produce a state-of-the-art electro-mechanical “smart” shunt to better treat hydrocephalus. Shunt obstructions, they discovered, are largely due to chronic shunt overdrainage.

Conventional shunts can inadvertently overdrain due to temporary ICP changes caused by daily living activities such as the patient standing, coughing, sneezing or playing sports. This major defect, Iskandar’s team believed, could best be overcome with a “smart” shunt that would activate only as needed, thanks to its ability to measure and take into account the patient’s dynamic ICP. The bottom line: hope for better shunt performance, far fewer shunt failures and surgeries, and less morbidity and mortality.

Isthmus Project learned about Madison Scientific, Inc (“MadSci”), the start-up company that emerged from Iskandar’s efforts, and recognized it as an opportunity that satisfies Isthmus Project investment criteria for medical innovation.

“We appreciate how Dr. Iskandar and his team were approaching an old problem in a new way and developing technology to support this novel perspective,” says Elizabeth Hagerman, executive director of Isthmus Project and chief innovation officer for UW Health. “This is exactly the formula for disruptive innovation.”

Repeated shunt surgeries have worn on Iskandar

Benny Iskandar has performed more than 2,500 shunt-related surgeries — most to repair failed shunts. After 26 years at UW Health, the emotional weight of having operated on so many children, many more than once, began to wear on him.

“I was frustrated by the repeat cycle of implanting shunts in these children only to see them return to the operating room because of device failure,” Iskandar says. “It made me feel that pediatric neurosurgery, as a field, was failing the younger generation of neurosurgeons and our patients.”

A decade ago, Iskandar formed the Wisconsin Hydrocephalus Project (WHP) team of UW experts including neurologists, physicists, neurosurgeons and engineers.

The Batterman family has generously supported the WHP research initiative from the get-go through the family’s Theodore W. Batterman Family Foundation. They later supported efforts to advance the SmartShunt Hydrocephalus SystemTM technology with a personal investment to MadSci.

A cure is the goal, but for now, a better shunt would be a godsend

“The truth is,” says Joseph’s mother, Angela, “we don’t really want a better shunt; we want a cure. But since we don’t have a cure yet, we want a better shunt.”

Following several years of research and development, the WHP team took the project as far as it could. To bring the SmartShunt System from the bench to the bedside, the team needed to work with a medtech company.

Tyler Wanke, MD, MBA, MEM, an accomplished medtech innovator who worked in Iskandar’s laboratory while a UW-Madison undergraduate was interested to learn more. The two sat down at a coffee shop, where Iskandar explained to Wanke his vision for a SmartShunt System.

After months of business plan development, including a top finish in a Northwestern University MedTech competition, MadSci was incorporated with the goal to further develop the SmartShunt Hydrocephalus System for commercialization. Subsequently, MadSci has successfully raised more than $1 million in private seed-round financing, including the Isthmus Project Investment and been awarded competitive Phase I and II NSF SBIR grants.

“We are excited,” Wanke says. “This really would be a game-changer that significantly improves the lives of hydrocephalus patients and their families.”

As Iskandar approaches the twilight of his career, he is more optimistic than ever about the potential impact of the SmartShunt System.

“This experience has given me the chance to reflect on the impact we could leave on this field and hundreds of thousands of families,” Iskandar says. “The status quo was unacceptable and now we are pushing the field toward a tangible turn for the better. I think we’re getting there.”